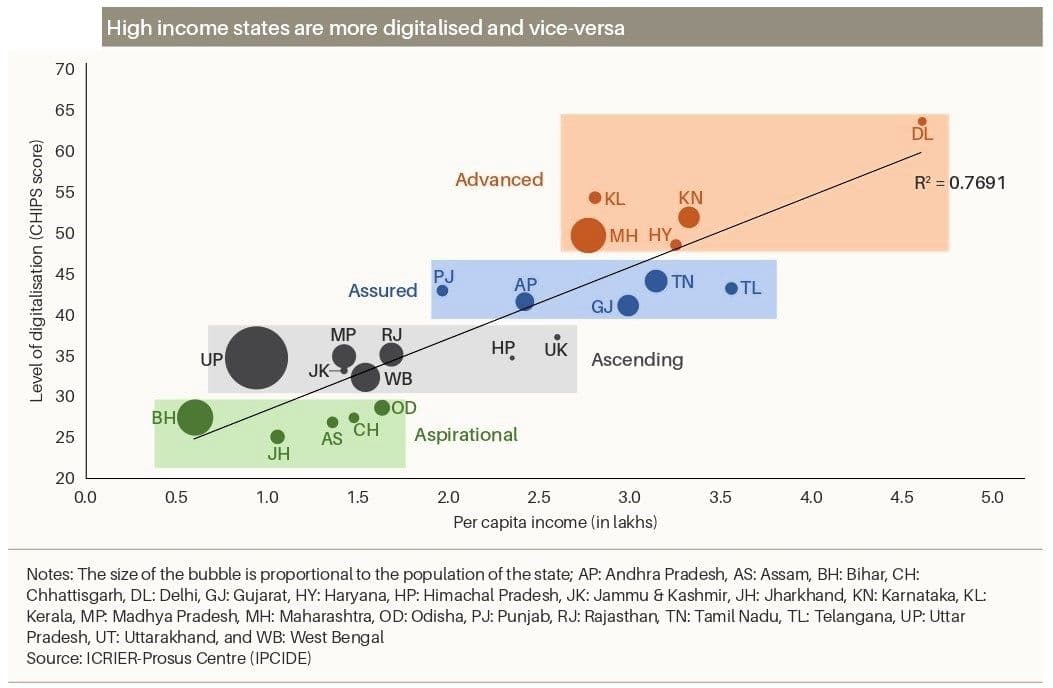

New Delhi: India may rank among the world’s most digitalised nations, but beneath this headline achievement lies a sharply uneven reality. A new study -- State of India’s Digital Economy: A Subnational Perspective,2025 -- reveals a country moving at multiple digital speeds, where a handful of states are approaching developed-country standards while others continue to struggle with fragile and uneven digital foundations.

According to the report, prepared by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), India is the third most digitalized country globally in aggregate terms, behind only the United States and China. However, when digitalization is assessed from the perspective of the average user, India slips dramatically to 28th place among the 33 largest countries by income or population. This striking disconnect, the study argues, is rooted in wide state-level disparities that have created digital “hotspots” and “dark spots” across the country.

The analysis benchmarks digital progress across 22 major states and 11 smaller states and Union Territories using the Connect-Harness-Innovate-Protect-Sustain (CHIPS) framework. This framework evaluates digital ecosystems through these five ‘pillars’, covering everything from access and affordability of connectivity to innovation, cyber protection and environmental sustainability. Together, these indicators capture not just the reach of digital technologies, but also how deeply they are embedded in economic and social life.

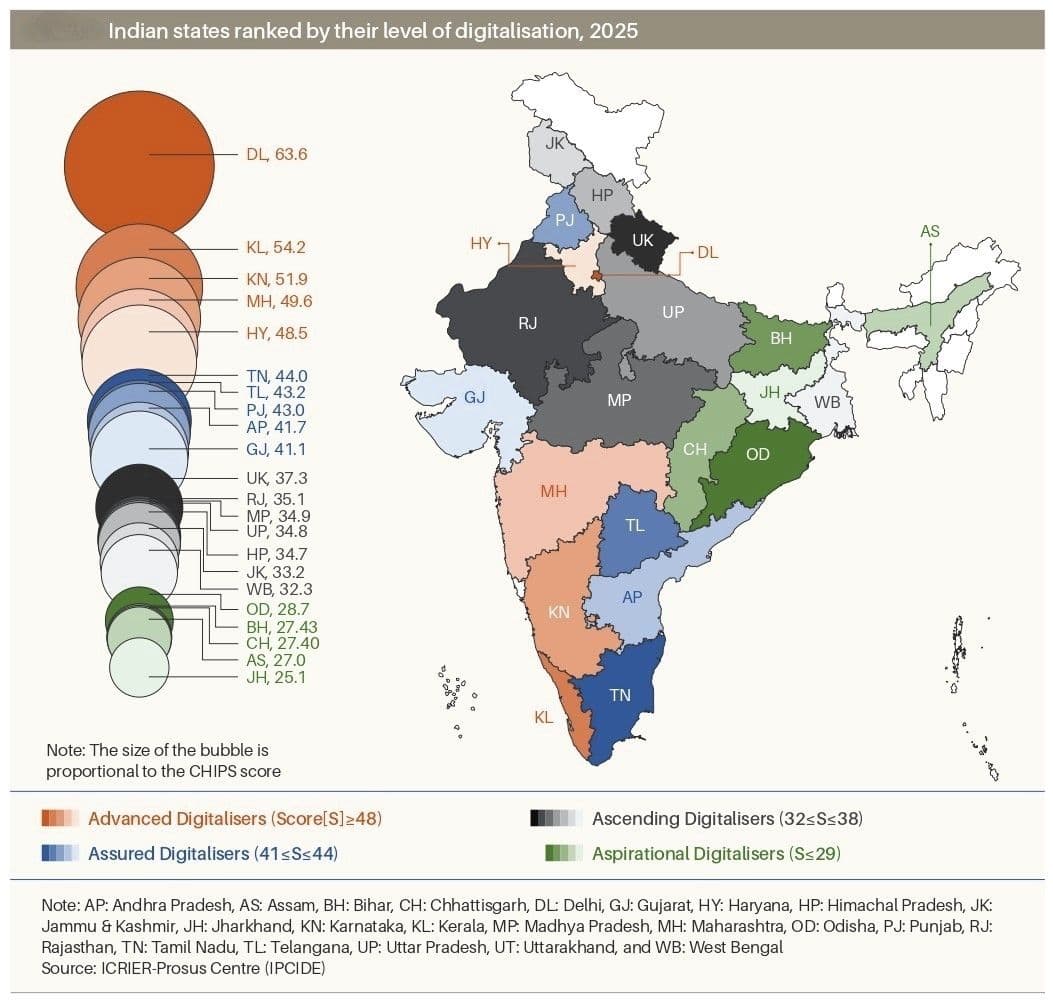

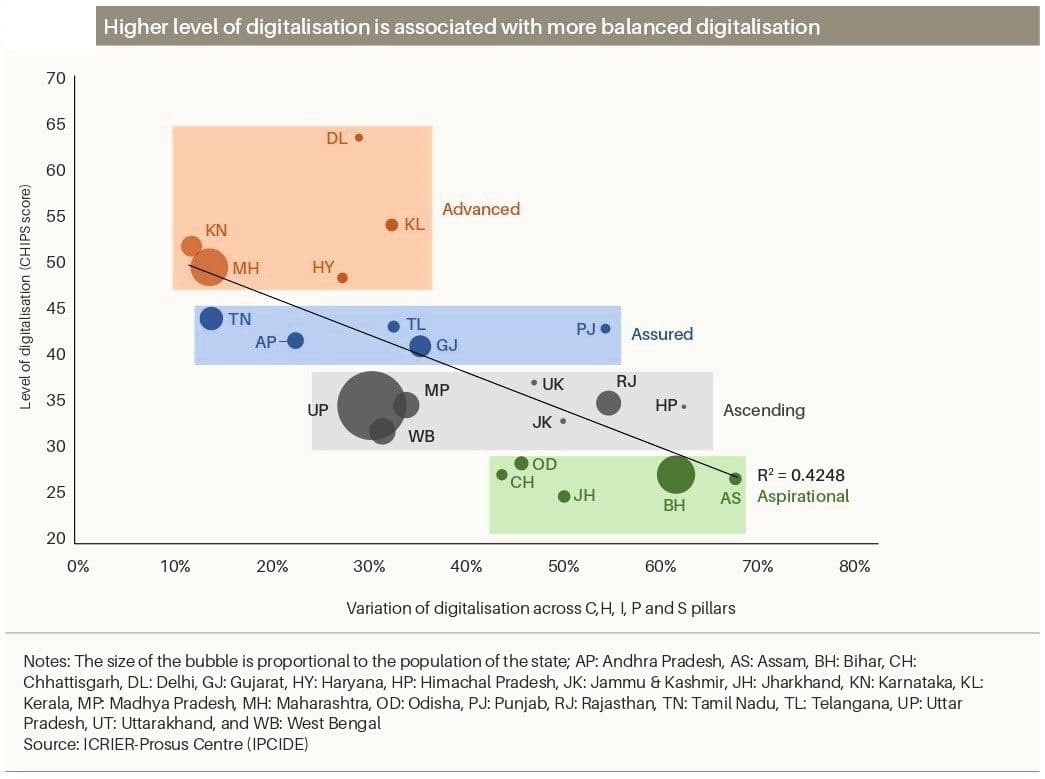

States cluster naturally into four groups. ‘Advanced’ digitalizers such as Delhi, Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Haryana lead across most dimensions, benefiting from strong infrastructure, digitally skilled populations and vibrant innovation ecosystems. Close behind are the ‘Assured’ digitalisers, including Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat, which follow similar trajectories but with greater variability in outcomes.

A third group of ‘Ascending’ digitalizers, comprising states such as Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal and Himachal Pradesh, shows strong momentum despite persistent structural constraints. At the bottom are the ‘Aspirational’ digitalizers — Odisha, Bihar, Assam, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand — where deep foundational challenges continue to hold back progress across most pillars.

Connectivity emerges as the single most powerful driver of digitalisation. The report finds an exceptionally high correlation between the ‘connect’ pillar and overall CHIPS scores, underlining the importance of access, affordability and quality of digital infrastructure. Nine of the top 10 states on the overall index also rank among the top ten for connectivity. Yet even in advanced states, smartphone penetration is beginning to plateau, pointing to lingering affordability barriers and usage challenges among the remaining unconnected populations.

Two Divides

The study also uncovers a tale of two digital divides. Gender-based digital inequality varies more between states than within them, suggesting that local social norms and cultural attitudes play a larger role than household-level differences. By contrast, the urban-rural divide appears to be a nationwide structural challenge. Gaps in access between urban and rural areas are as large within states as they are across states, reflecting common constraints related to infrastructure quality, service availability and costs.

One of the report’s more surprising findings concerns the ‘Harness’ pillar, which measures how effectively digital tools are used for private and public purposes. Several Assured and Ascending digitalizers, including Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh, outperform richer and better-connected states on this dimension. The widespread adoption of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) has played a decisive role, lowering transaction costs and enabling more targeted service delivery in areas such as health, education, welfare and finance.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, economic prosperity is no longer the primary determinant of digital participation. Richer states do not necessarily use private digital platforms more intensively, nor do poorer states rely disproportionately on public platforms. Instead, both private apps and government-backed platforms have diffused widely across income levels. What matters more, the report suggests, are digital and financial literacy, as well as user skills.

Important Asymmetry

There is, however, an important asymmetry. While poorer states are rapidly catching up with richer ones in the use of private digital platforms — often driven by entertainment and social media — no similar convergence is visible for public platforms and DPIs. This reflects the utilitarian nature of public digital services, which are not designed for universal or discretionary consumption.

Innovation remains the most geographically concentrated pillar of all. States hosting major IT hubs, notably Delhi, Karnataka and Maharashtra, continue to attract the bulk of startup investments. Knowledge production, measured through universities, innovation labs and patent activity, is more evenly spread, but many states struggle to translate this intellectual capital into startup funding and entrepreneurial scale. As a result, the gap between the best and weakest performers on innovation is wider than in any other pillar.

Interestingly, the protection pillar tells a counterintuitive story. States that rank highest in protecting residents from cyber risks are not the most digitally advanced. Rajasthan, Assam, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar top the protection rankings, largely because their lower levels of digital activity reduce exposure to cybercrime rather than because of superior defensive capabilities.

Overall, the report paints a picture of an India that is digitally ambitious but deeply uneven. While leading states are building globally competitive ecosystems, large parts of the country risk being left behind. Enabling weaker digitalizers to converge with the rest — through better connectivity, skills, and the diffusion of effective policies and practices — will be critical if India is to realise its aspiration of becoming a global digital powerhouse in the age of artificial intelligence.