Photo courtesy: PickPic

New Delhi: The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) World Energy Outlook 2025, released Wednesday, captures the turbulence and transformation defining the global energy system — a system in which oil remains both a stabilizing force and a source of fragility. The report paints a world where geopolitical fragility, resource competition, and uneven progress on decarbonization have converged to make energy not merely an economic commodity but a cornerstone of national security and strategic influence.

Oil, despite its cyclical abundance and periodic price slumps, still lies at the heart of global power politics. It underpins fiscal stability in exporting nations, fuels military and industrial might, and anchors the geopolitical calculations of both established and emerging powers. Yet this centrality is now shadowed by new vulnerabilities: climate disruptions, cyber risks, and the weaponization of trade in both hydrocarbons and critical minerals. The IEA’s findings make clear that the energy order that shaped the 20th century is being redrawn — not replaced, but reconfigured into a more complex web of interdependence and competition.

Geopolitical stakes

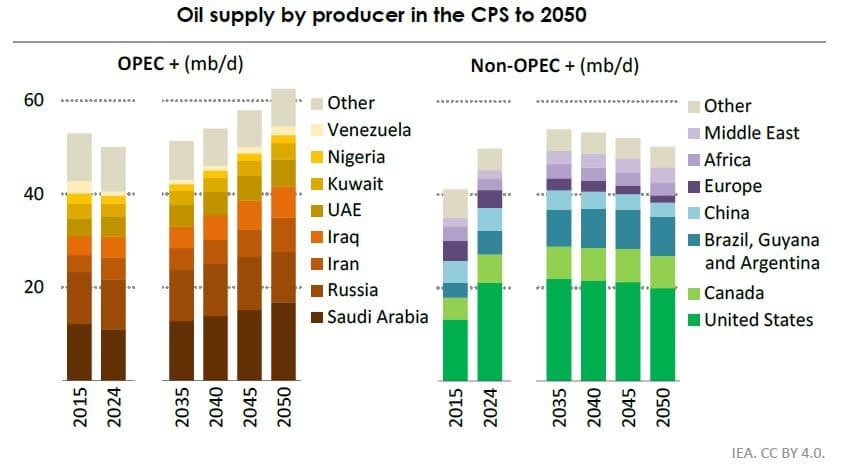

Amid subdued oil prices, the geopolitical stakes remain high. Traditional producers in the Middle East, North America, and the emerging basins of South America hold the short-term advantage of abundant supply, but their influence is being tested by policy shifts and technological disruption. The United States, Canada, Guyana, Brazil and Argentina together form a “quintet of supply”, capable of offsetting market tightness and keeping prices moderate. Yet the IEA warns that this apparent comfort masks deeper instability: the decline of mature fields, the growing politicization of energy trade, and the fragility of a market where conflict and climate alike can trigger cascading shocks.

Meanwhile, energy-importing nations are pursuing divergent strategies to secure affordability and resilience. Many turn toward renewables, electrification and efficiency, while others cling to traditional fuels as insurance against volatility. The result is not convergence but fragmentation — a patchwork of national strategies competing within an increasingly interconnected system. “Governments are contending with a formidable array of potential threats, vulnerabilities, dependencies and uncertainties spanning areas such as oil, natural gas, electricity, energy infrastructure, critical minerals, technology supply chains, data centres and AI, and more,” says Fatih Birol. IEA executive director.

Age of critical minerals

If oil once symbolized industrial progress, critical minerals now represent the new frontier of geopolitical tension. The IEA’s 2025 analysis underscores that a single country — China — dominates refining for 19 of the 20 most strategic energy-related minerals, with an average market share of around 70%. These materials — vital for batteries, grids and electric vehicles — are also indispensable to AI chips, defence systems, and advanced manufacturing. This concentration of power marks a profound shift in the locus of energy vulnerability: from the Middle Eastern oil fields of the past century to the mineral refining plants and export chokepoints of East Asia. China’s recent export controls on rare earths and battery technologies highlight how minerals have become instruments of statecraft, much as oil once was. For consuming nations, diversification of supply chains is not merely an economic imperative but a matter of strategic survival.

The report also situates oil within a broader narrative of accelerating electrification. The ‘Age of Electricity’, as the IEA terms it, is already here. Global electricity demand is growing far faster than total energy use, powered by the proliferation of electric vehicles, data centres, and air conditioning across both advanced and emerging economies. Yet the infrastructure to deliver this power is lagging. While annual investment in generation has soared to over $1 trillion, grid investment trails far behind, creating congestion, bottlenecks and price volatility. This imbalance mirrors the broader contradictions of the energy transition: technological innovation outpacing institutional and physical readiness. For all the advances in renewables and batteries, the world’s appetite for fossil fuels remains robust — oil, gas, and coal consumption all reached record highs in 2024.

No let up in oil demand

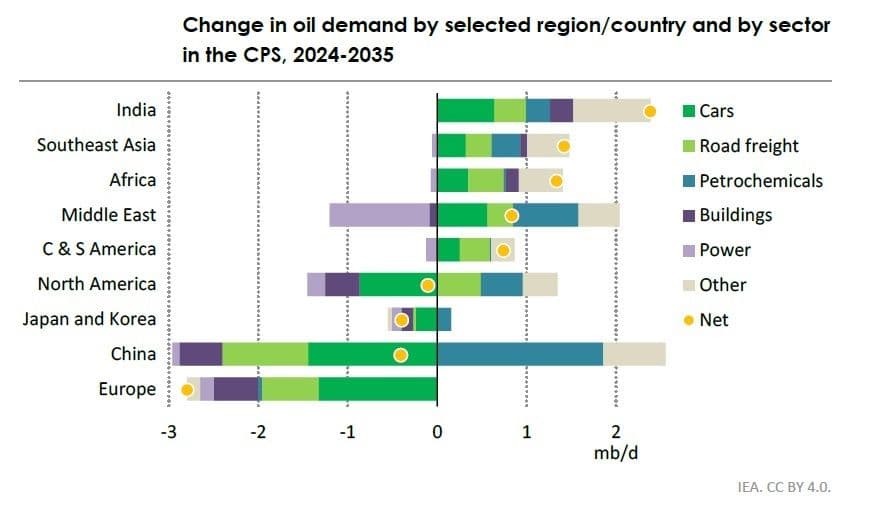

Oil’s future, as the IEA makes clear, will be defined by policy and perception as much as geology. In its Current Policies Scenario (CPS), oil demand continues to grow through mid-century, driven by industrial and transport needs in emerging economies. In the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), demand plateaus around 2030 before entering a slow decline, reflecting incremental progress on clean energy goals.

Only in the Net Zero Emissions (NZE) pathway does oil use fall decisively, but even there it retains a structural role in sectors where electrification is slow or impractical. These scenarios reveal not just alternative energy futures but competing political visions: one of continuity and control, another of adaptation and compromise, and a third of transformation that demands unprecedented global coordination.

“Today, the risks that we identified in 2021 are no longer a theoretical concern; they have become a hard reality. The implications spread across different energy technologies but also apply to other strategic sectors such as energy, automotive, AI and defence. They affect millions of jobs… Urgent action is needed both in the near term to strengthen preparedness against potential disruptions, and over the longer term to diversify supply chains and reduce structural risks,” says Birol.

World energy security

Ultimately, the World Energy Outlook 2025 situates oil within a fluid and fractious geopolitical landscape, where energy security and climate action are no longer separate agendas but intertwined challenges. The forces shaping energy markets today — regional conflicts, trade fragmentation, and technological acceleration — are rewriting the rules of power. The traditional oil-based order is giving way to a hybrid system where hydrocarbons, critical minerals, and digital infrastructure coexist in uneasy balance. Yet through all its scenarios, the IEA offers a sober reminder: even as the world electrifies, oil’s shadow stretches long.

It remains the ultimate test of whether nations can balance short-term security with long-term sustainability and whether geopolitics can evolve as fast as the energy system it seeks to control.