New Delhi: When ChatGPT became public in late 2022, it was greeted with curiosity, excitement and also with a touch of unease. Few, however, predicted how quickly it would ripple across the global labour market. New data compiled from millions of online job postings shows that artificial intelligence (AI) is not just another digital tool. It is a force that is simultaneously opening lucrative new opportunities while eroding demand for the kinds of office jobs that once defined the middle class.

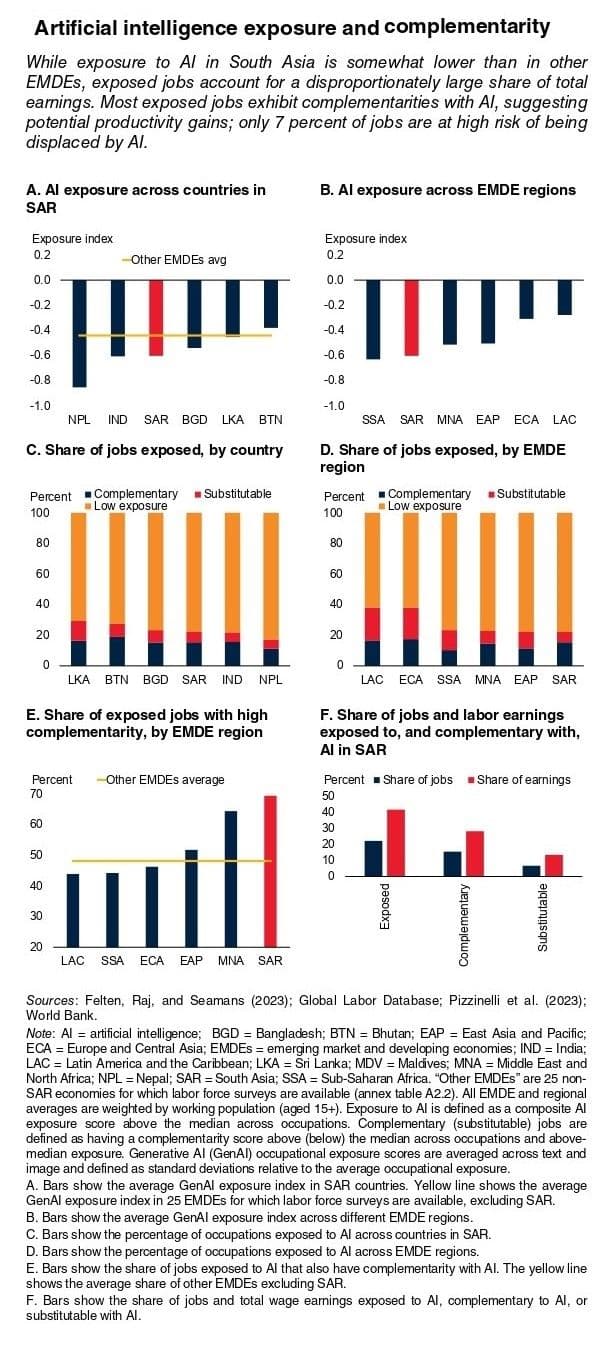

The World Bank’s latest South Asia Development Update traces this shift in striking detail. Between January 2023 and March 2025, the share of job listings requiring AI skills more than doubled, rising from 2.9% to 6.5% of all postings. Demand for AI-skilled workers grew 75% faster than demand for everyone else.

The most sought-after competencies range from traditional machine learning and neural networks to cutting-edge areas like natural language processing and generative AI. Crucially, each one of these skills exhibits the same timing: an abrupt acceleration after ChatGPT’s release.

Despite the headline numbers, the surge is not evenly distributed across the region’s economy. AI hiring remains concentrated among high-skill, white-collar, urban roles rather than spreading widely across industries. Tech-enabled services, finance, consulting and specialised engineering dominate demand.

In South Asia, two countries — Sri Lanka and India — account for most AI-related openings. And within India, the pattern is even more geographically concentrated. The ‘southern technology corridor’, led by Bengaluru and Hyderabad and followed by Pune and Chennai, has become the regional hub for AI hiring. For both countries, AI is not merely a technological upgrade; it is becoming a competitive advantage in global services.

The rewards in this AI-focused job market are significant. Employers are paying far more for these skills: a job requiring AI expertise commands a 28% wage premium. By comparison, jobs requiring general digital abilities offer only a 12% premium. It is the clearest monetary signal yet that AI capability has become one of the fastest ways to climb the wage ladder — if you can acquire it.

Skewed Demand

The growth of AI jobs tells only half the story. Running in parallel is a quieter, but equally consequential shift: job growth is slowing sharply in roles that AI can automate.

Across occupational categories, the jobs most exposed to AI have grown far more slowly between 2020 and 2025 than jobs with low exposure. The divergence becomes dramatic after late 2022. The occupations least exposed to AI roughly quadrupled their job listings over this period, while the most exposed expanded only half as fast. In other words, demand is still rising across much of the white-collar economy, but not for everyone.

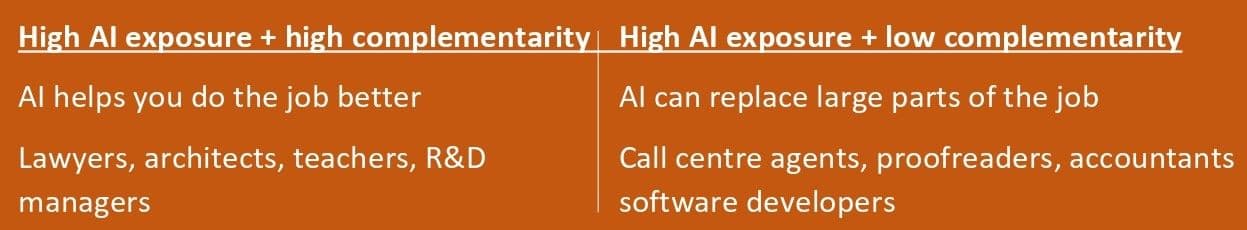

The crossing point lies in whether AI replaces tasks or complements them. Software developers, call centre agents, accountants and proofreaders represent roles whose day-to-day tasks overlap heavily with what generative systems can now perform reliably and at scale. These jobs display high exposure and low complementarity. For them, job postings dropped almost immediately after ChatGPT became mainstream.

The fall in demand was steepest for call centre workers, an anchor of white-collar employment in South Asia, where postings fell 24% relative to lower-exposure occupations, the report says.

But roles like lawyers, architects, teachers and research managers — equally exposed to AI but whose work requires persuasion, creativity, interpersonal judgment and domain expertise — did not see a similar fall. AI enhances productivity in those professions rather than replacing them. Demand therefore continues along its earlier trajectory.

These diverging trends point to a deeper reordering of work: AI is beginning to reshape not which sectors grow, but which tasks survive.

Losing ground

The turbulence is not evenly distributed across experience levels. It is not senior professionals who are seeing their roles squeezed first, but the younger and mid-tier workers standing at the start of their careers. The data shows that after the introduction of generative AI, job postings for roles requiring only a secondary-school qualification fell by 24% across the AI exposure range. Meanwhile, roles requiring university or graduate education detected no significant decline.

This is a shift with deep social consequences. For decades, white-collar entry-level jobs — call centre agents, junior software developers, back-office support, proofreading assistants, accounts executives — formed the core of upward mobility for millions of middle-class aspirants in the region. They offered on-the-job training and a ladder into better-paid positions. But the ladder is becoming steeper.

When AI can perform 60% to 80% of the daily workload of junior knowledge workers, employers reduce hiring not because the work disappears, but because fewer people can manage far more.

The business-services export sector makes this trend visible. It is one of South Asia’s fastest-growing industries, supporting global companies with IT, customer support and back-office functions. By March 2025, 12% of business-services job ads required AI skills, compared with 4% in other sectors. Yet hiring in business services has slowed dramatically since ChatGPT’s emergence — growing 35% more slowly than other sectors — and wages have fallen by 8% relative to the rest of the market. The combination of rising output but slowing employment is a classic sign that technological automation is beginning to substitute human labour.

India’s Gamble

India is at the centre of this transformation. For two decades, no country capitalised on the outsourcing boom as successfully. The BPO and IT services industry generated millions of stable, upwardly mobile jobs for college-educated youth. Now, the very tasks that made India a global services leader — standardised coding, documentation, records processing, customer support — are among the most automatable in the age of AI.

If generative AI continues advancing at the pace of the past two years, India faces two paths. Down one path lies displacement: with foreign firms adopting automation aggressively, outsourcing hubs could lose their competitive advantage if routine service work is handled algorithmically rather than offshore. But down the other path lies significant opportunity.

India’s largest technology firms are already climbing towards higher-value functions like research outsourcing, data analytics, product design and AI-enabled consulting. The shift marks a move from business-process outsourcing to knowledge-process outsourcing — from following instructions to solving unstructured problems.

The early signals are encouraging: productivity in the technology-services sector is rising, and exports continue to grow robustly even as the pace of hiring slows. If this pattern holds, India could become a world centre not only for the supply of digital labour but for the development and integration of AI-augmented professional services. The transition will not be automatic, however. It depends on how quickly the workforce can absorb new skills and on whether opportunities expand as rapidly as automation compresses entry-level hiring.

AI is not simply adding jobs or removing them. It is polarising the white-collar economy. At the top, where human expertise combines with AI capability, wages and opportunities are accelerating. In the middle, where work is routine, codifiable and predictable, hiring already shows signs of contraction. At the bottom, young people seeking their first foothold in professional life are finding that the goalposts have moved further away.

For workers, the message is unsettling but not hopeless. AI is replacing routine thinking, not human thinking. The jobs that thrive will be those grounded in creativity, complex judgment, relationship building and the ability to use AI as a partner rather than a competitor.

For South Asia — particularly India — the next decade will determine whether generative AI becomes a springboard into higher economic value or a bottleneck that shuts newcomers out of the workforce.

The future of white-collar work has already arrived. It looks less like a robot takeover, and more like a race — between those whose skills AI automates, and those whose skills AI amplifies.