Much before US President Donald Trump’s decision to increase H-1B visa fees to $100,000 from the existing fees ranging between $2,500 and $5,000, the red line was drawn when he hosted 33 Silicon Valley leaders (including five Indian-origin top executives such as Sundar Pichai and Satya Nadella) at the White House. Although the meeting was about artificial intelligence and US investment, behind the scenes the talk was about a paradigm shift —how AI programming tools can now generate thousands of lines of code quickly, reducing demand for junior software engineers.

This may explain why US tech giants such as Amazon, Intel, Meta and Microsoft have been consistently laying off workers in recent times, particularly before the hike in the H-1B visa fees. Even in India, the top six IT firms added just 3,847 employees in Q1FY26, a 72% drop from Q4FY25. TCS made national headlines for laying off 12,200 employees, which is about 2% of its global workforce.

India Largest Beneficiary

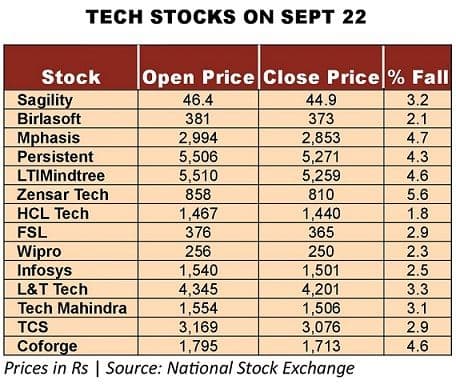

Although we are worried about the fate of around 400,000 Indian IT workers who are likely to see their H-1B visas not getting renewed in the event of this visa fee hike, sooner or later such a thing was bound to happen. Region-wise, India was the largest beneficiary of H-1B visas, accounting for 71% of 3,99,395 in H-1B visas 2024, while China was a distant second at 11.7%. Market participants had anticipated a sharp fall in stock prices of Indian IT companies heavily reliant on the US market. By the end of trading, these stocks declined an average of 3.4%.

AI, automation and cloud computing are changing the face of tech hiring, something which came too quickly, especially when there is a growing pool of computer science graduates specializing in coding that has been growing over the years. Graduating with a degree in computer science became a fad, with top tech executives, billionaires, and even US Presidents promoting the field and encouraging students to learn coding. Throughout the past decade, a degree in computer science was yielding results, with fresh graduates in the US starting off with salaries exceeding $100,000, plus substantial bonuses and stock grants. Same trends were noticed in India and elsewhere across the globe.

Excess Supply

Like in the US, in India, there is a craze for admitting students to computer science programs, with recent data suggesting India is producing in excess of one million engineering graduates every year. This has led to excess supply, particularly in the age of AI driven technological change. This is akin to the cobweb model in economics, where farmers grow a particular crop in response to higher price signals in the present period, only to realize there is excess supply in the next period.

We are witnessing similar event now but spread across a longer time horizon to adjust for the technological change. Entry-level hiring by Indian IT firms has dropped 50% from pre-COVID levels. During 2021 and 2022, employment generation in the organised sector fell to less than one lakh jobs a year, which is less than 25% of the annual employment generated before 2011. Daily, less than 2% of Indians who apply for jobs get them. Presently, India (like elsewhere in the world) is slowly transforming into a gig economy where the labour market is increasingly characterised by the prevalence of short-term contracts or freelance work as opposed to permanent jobs. A study by KellyOCG, a global recruitment company, shows that 56% of Indian companies have more than 20% of their workforce as contingent workers. In fact, most of the hiring in manufacturing, whether by the government or by private corporate enterprises, is now being increasingly outsourced to private contract suppliers.

That things change so rapidly, requiring adjustments from both industry and the education system, is not new. Even the advent of computers and technology that marked the rise in productivity during the last century required adjustments. Alongside computers, electricity, combustible engines and refrigeration aided economic growth through a more productive labour force and necessary training. This has led to the creation of thousands of jobs in manufacturing.

Difficult Transition Phase

In the age of big data analytics, machine and deep learning, things are a little different with an apprehension that machines are increasingly taking over jobs performed by humans. But that is entirely not true. Newer types of jobs are opening up and it is in this transition phase that things will be little difficult.

According to a report from the US Federal Reserve Bank, among college graduates aged 22 to 27, computer science and computer engineering majors are facing some of the highest unemployment rates, ranging between 6.1% and 7.5%, respectively. That is more than double the unemployment rate among recent biology and art history graduates, which is just around 3%. In an ironic twist, job applicants leverage AI tools such as Simplify to mass-customize their resumes and applications, only to have companies use similar AI technology to automatically screen them out.

The silver lining for India is that irrespective of Trump's hike in visa fees, it will lead to more offshoring. The labour cost is still lower in India, and with a high number of STEM graduates. It will only bolster investment in global capability centres (GCCs). India accounts for 55% of the world’s GCCs, employing around 1.9 million people, with these numbers likely to grow further in the near future.

(The author is Professor, School of Management, Mahindra University, Hyderabad)